The Back Up Trust is a charity that does important work supporting spinally injured people in the UK, with a focus on helping them lead active and fulfilling lives. I have benefited from quite a few of their services since leaving hospital, including five days spent in Leeds last summer on a “skills for independent living” course. This helped build confidence, and showed me some techniques for navigating my new life.

Last week I attended their seven-day “multi activity” programme based in the Lake District. This is something I had wanted to sign up for since I found out about it last year, although always with a serious degree of trepidation. Much of that, it turns out, well justified. Still, I learned a few things in the process. Feel free to look over my shoulder as I try to work out my thoughts on the page. Or, y’know, go and do something more interesting with your life.

*

Prior to leaving I had tried to build this trip up (to myself and others) as my chance for a holiday. Realistically, my only chance for a holiday this year. It is now so difficult for me to be away – not just because of the massive logistical constraints, but having to negotiate away-from-home care cover via NHS bean counters – that a specially organised trip, run by a spinal charity, represented the only serious option for extended time not in London. So I was very glad to take it. But having made it there and back, it is hard to describe my week away – welcome and much needed as it was – as a holiday.

We stayed at the Calvert Trust near Keswick, a specially-run centre which aims to enable people with disabilities to access the outdoors. Obviously, this is a great thing. Without it, I myself wouldn’t have been able to spend a week in the Lake District. They provide not just accommodation, but accessible transport to various locations, and a team of staff who specialise in supporting people with disabilities. For this, I’m grateful. But the thing is, spending the week in a disabled facility it is not exactly conducive to making you feel like you’re on holiday. Maybe it’s just because I’m not used to being disabled yet. But seeing various bits of adapted equipment everywhere, with lots of pictures on the walls of happy smiling disabled children, and indeed sharing the canteen some days with groups of kids with mental disabilities – this is not exactly a recipe for “getting away from it all”.

Similarly, because the Back Up group consists of many people with spinal injuries (both participants like myself, but also group leaders and skills trainers who are themselves injured), conversation tends to revolve around the various aspects of spinal injury. Bowel programmes, wheelchairs, pressure sores, care cover, level of injury – topics like these dominate. Not least because it’s not clear what else you’re going to talk about. There is often an assumption that if two people have a spinal injury, then they will therefore have something in common, and be friends. But it really does not work like that. Spinal injury hits a random cross-section of the population, and I don’t have much in common with random cross-sections of the population (nor they with me). Which makes for quite a contrast with what you would usually call a holiday. Normally, you go on holidays with friends, or with groups of people you expect to have something in common with, and can potentially form friendships off the back of. By contrast, a random bunch of SCI survivors thrown together is not the disability equivalent of club 18 to 30.

Although by the end of the week there were a couple of people I connected with, and that was good, the overall effect did not generate a holiday feel. It was rather to be constantly reminded that I have a fucking spinal cord injury. Not so long ago I slept in Alpine huts at 2000 meters after hours-long hikes, or in a van I’d driven for hundreds of miles so I could get up and climb. Now I share adapted facilities with the mentally disabled, whilst listening to people discuss the finer points of sticking suppositories up their arses. Don’t get me wrong, it is of course a good thing that people with all different kinds of disabilities should be able to access somewhere like the Lake District. It is great that the Calvert Trust exists. But for me, whatever my time there was, it wasn’t a holiday.

*

OK, but what about the actual course content, the “multi-activity” access to one of the most beautiful parts of the country? I knew in advance that this was going to be hard. After all, I spent a lot of time in the Lake District prior to my personal disaster: climbed some of its most beautiful routes, spent long days in the mountains, alone or in the company of people I care about. Returning in a wheelchair was never going to be easy, and I was pretty sceptical that the “adapted” activities on offer would help reconcile me to this new life. And in many ways it was even tougher than I had expected.

Even just arriving there was mentally difficult. As my train started pulling through Cumbria, I looked out of the window at fields: fields of lambs, drystone walls, oak trees, and that mountain grass you only see at higher elevations. Watching as the scenery changed my mind went back to driving up the M6, on so many previous occasions; to when I knew what it felt like to be happy. Emerging from the station at Penrith reminded me that the last time I was in this very spot I was meeting a friend with whom I would spend a week climbing classic Lakeland routes. That was about three weeks before the catastrophe that changed everything. Classic routes on the same list of “must do” climbs that led me to that cursed mountain in Scotland. The word “triggered” gets overused a lot these days, but it's hard to think of one that fits better.

On the first day of the course proper, the morning was given over to wheelchair skills in the on-site sports hall at the Calvert Trust. As we rolled into the gym I did my best to try and ignore the climbing holds dotted up the walls; the top ropes rigged in place; the anchor set ups allowing beginners to get their first tastes of the sport. Not a proper climbing wall, just an introductory set up aimed at kids. But close enough to the real thing for long-suppressed feelings to swell. Averting my eyes, I tried to get involved in the wheelchair skills, despite having little here to learn (when you spend all day in a wheelchair, there’s not much that an introductory session aimed at all abilities can teach you). Throughout, I pushed down the nagging thought that outside the weather is beautiful, that just down the road is world class climbing – and here I am, sat indoors, a fat cripple in a wheelchair, who threw it all away. Taking a break, we shuffled outside to the car park. I gazed across Bassenthwaite, at the ridgeline high above. Just another place I will never now go.

*

That afternoon at least presented the opportunity to get further afield. An old railway line between Keswick and Whitehaven has been tarmacked for about 10 miles, now making up the start of the famous Coast to Coast cycle route. We were dropped off at a section about 3 miles from Keswick, allowing us to push mostly downhill: through the valley, over the river, between the trees. It was undeniably beautiful. And what I wanted more than anything was to experience this alone. The way I would once have hiked solo for hours when there was no one to partner up and climb with. The chance just to enjoy the peace, the beauty, the serenity. But I’m never alone these days. Much as I tried to stay a little distance from the main group, the endless chitter chatter of SCI survivors was never far away. And again and again, I saw that patronising look cross the faces of people coming the other way. “Oh wow, a group of people in wheelchairs. Isn’t that just wonderful!” There is an awful lot to hate about spinal cord injury. For me, being an object of condescending pity is pretty high up the list. But that’s just the way it is now. So I did my best to let it go.

*

Day two, and things did not get much easier. We travelled out of the National Park to an old disused airfield, now part nature reserve, part cycle track. The aim was to have a go at hand cycling, although I quietly suspected I was going to have no truck with this. Nonetheless, I wanted to at least give it a fair crack. Hence, I submitted to a team of six people trying to wedge a sling under me, before lifting me out of my wheelchair into various cobbled-together contraptions. All with predictable results. Either my legs were too long, and prevented me turning the hand cranks, or my useless non-gripping hands could not be strapped securely in place on the handles. And so I spent most of the day in the café, reading Free by Amanda Knox. (Now there is somebody who has been through a hell which she did not deserve. Funny the people one comes to identify with.)

*

Having been told what was on the agenda, I knew that day three was going to be the toughest so far. A morning spent doing “rock and ropes”, in the sports hall. Translation: get hoisted by other people in some silly parody of rock climbing. Still, I thought I should at least give it a try. Positive mental attitude and all that. So along I went. And lasted about 10 minutes.

When I wheeled into the sports hall, the first thing I saw was a huge collection of locking carabiners. Different sizes, different shapes – but the first time I’d seen proper climbing equipment since that day two years ago. And behind them were various belay devices; a Grigri; traction equipment. Ropes.

I used to love my gear. I cherished it, valued it. Was actually a little obsessed with it. And just like my old home, and my van, I never got to say goodbye to it. My parents gave it all away, long before I left hospital.

But the worst was when I was given a helmet to hold (or rather, to cradle in my lap). Just a standard issue Petzl lid, of the kind used in every climbing centre in the country. I have seen a thousand of them before. And all I could do was stare at the logo. Think of the Petzl gear I used to own. That the last time I touched a climbing helmet, it shattered in two such was the force exerted by my landing on my head.

An instructor started saying something to me, but it was more than I could take. I shoved the helmet into his confused hands, and made for the door. Finding as quiet a place as possible, I sobbed into my knees. A little while later, one of the Back Up team came to speak to me. 10 years my junior, he’s already nearly a decade out from his injury. And he gets it. A former semi pro mountain biker, he broke his neck in a freak crash 100 meters from the end of an easy run. And he’s worse off than me. I might not be able to use my hands, but I can at least move my arms. He doesn’t even have that. “The grief never goes away”, he said, “but it does get easier with time”. How long? I implored. “I’m afraid only you can find that out.”

*

That afternoon we went down to Keswick, for a gentle push around some accessible bits of Derwent water. Pretty, scenic, pleasant. But also just so tame. In the distance, I could see the fells. I knew that if following the road around the lake, one would pass Shepherd’s Crag on the left, home of some great single pitch classics. A little further, Troutdale Pinnacle. Around the corner, the village of Grange, with the Climbing Club hut I stayed in on my last visit. A little further takes you to the YHA accommodation with the decent bar and food, and the neighbouring campsite I once visited with the North London Mountaineering Club, back when I was president. Borrowdale, where I once had so many plans. On through to Scafell, and some serious mountain classics. Broken dreams, scattered down a Lakeside coast. Beside me, unknowing tourists licked their ice creams. At least this time I managed not to cry.

*

Day four, and something a bit different. Canoes rafted together, a gentle paddle down Bassenthwaite. Of course, I was again basically useless: unable to hold a paddle, and strapped into a supportive seat so high I couldn’t have reached the water anyway. And all of this only following the faff that is now parr for the course when it comes to “adapted” activities. Think: the best part of two hours just to get four cripples into two boats. During which I could of course contribute nothing; merely sit there, a useless lump of meat, watching.

Still, it was good to be out on the lake. A bit chilly, but tolerable in the sun. Also, I realised that I wasn’t really bothered that I couldn’t paddle, because I’ve always thought that paddle sports are boring anyway (so much effort to go so little distance, so slowly). Hence whilst I’m not sure it counts as an “activity” when you just sit there and do nothing, it was nice to be out in the open air. That is, until it was time to disembark. Due to the exceptionally low water levels following the recent dry spell, somehow a mistake was made, and my canoe was allowed to topple over – with me still attached. I was never in any danger, because the water was so shallow, but I did get completely soaked from head to foot. So whilst everyone else went to the nearby pub to sit in the sun, I had to be strapped back in the bus, and taken to get changed into dry clothes that wouldn’t wreck my pathetic neurogenic skin.

A nice day, cut short. That left one to go. On the agenda? Abseiling.

*

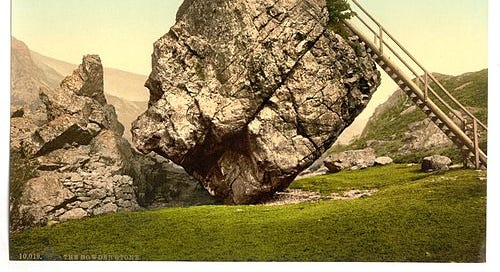

Of course I thought about pulling out. I didn’t want a repeat of the morning in the sports hall. But there was a bigger part of me that genuinely wanted to go. I knew the venue was going to be the quarry by the Bowderstone, in Borrowdale. I’ve been there before; I knew what to expect. Last time I was in the Lake District, I’d even checked out that very abseil spot, musing that it must be used by children’s groups and for people with disabilities. Strange to think that the next time I’d be seeing it, it would be from a wheelchair. But as odd as it may sound, I yearned to see rocks; to once again be at the foot of a crag. And so I willingly went along.

As usual there was the mandatory fannying about. I think it took about four hours for three people to do a 15 meter abseil. Such was the complex rigging and mechanical set up required to hoist people out of wheelchairs, over the cliff edge, and down to the bottom. (Amongst climbers abseils are notoriously time-consuming, but this was something else.) Nonetheless, I used the waiting time as an excuse to help get pushed along to the Bowderstone itself – an infamous Lakeland bouldering venue, covered in very hard problems. The last time I was here, I played around and failed on some of the “easier” climbs. Later that evening, a few of us had gone up the artificial staircase to the top, drank beers as the sun went down. Those memories were of course now bittersweet, but in a strange way it felt therapeutic to sit at the bottom of a boulder and look at the chalked-up holds, see the eroded patches where mats have long been piled. Nostalgia tinged with sadness, but nostalgia nonetheless.

When it was my turn, it certainly felt strange to abseil. Not least because I had to exit the cliff facing out, such was the necessary rigging for gaining clearance of the edge. And truth be told I wasn’t really abseiling anyway, because my lack of grip function meant that I couldn’t release the rope myself. I got lowered by the instructors – but I knew that was always going to be the case, and so it hardly bothered me. On the way down, however, I asked them to pause and let me face the rock. For a few seconds, I let my eyes wander across the quarry face. I found cracks and imagined the gear they would take. I saw the layback holds, and pictured the moves that would be required to link sections on the adjacent bolted sport route. Briefly, fleetingly, I was reconnected to my past life. I sat back in the harness, being lowered to the ground, and for a moment remembered just how good this once felt.

At the bottom we sat in the shade, eating sandwiches as the instructors packed away the mountains of gear. I looked up through the trees and could see the outlines of rocks, trace potential routes through the edges and holds. Again, I was reconnected to the past. Just sitting at the bottom of a crag on a beautiful summer’s day, chatting away in the kind of place I’ve long loved best. A sadness, for sure. But also a catharsis, nearly two years overdue.

*

Before taking this trip, I told myself that if nothing else it would be good to get back to the mountains. But this was naïve. The mountains stayed out of reach, almost out of sight. A bunch of people in wheelchairs can only go to certain kinds of places, after all. The mountains will have to wait a little longer, require a different kind of approach.

If nothing else, however, the trip confirmed to me something that I’ve long been suspecting. Namely, that I don’t get on with “adapted” activities. In part this is just because my level of disability is pretty extreme, and there isn’t much that can be meaningfully adapted in ways that make me still want to do them. I really hate the idea of doing pantomime imitations of activities that non-disabled people can do. Perhaps this wouldn’t be so bad if I could at least enjoy the process of exercising. But the disconnection of my sympathetic nervous system from my brain means it is now impossible for me to physically enjoy exercise: to get my heart rate up above 120, to sweat, to feel like I’m actually trying in a satisfying way. The truth is I don’t want to do “adapted” sports. I want to do real sports. I want to climb. I want to run. I want to hike. I want to cast a fly line by myself in the wilderness, with nobody else for miles. But given that I cannot do these things, the answer is not to try and replace them with (what are to me, at least) parodies. Other people can of course do what they want, whatever brings them joy. But “adapted” won’t work for me – or at least, not that I’ve found so far. Of course, maybe one day I’ll stumble across something that does click, that fills the hole that climbing has left behind. But I suspect not. And if not, so be it.

As for climbing, if nothing else that last abseil at least felt like an overdue step in the process of finally saying goodbye. It hurts. It really hurts. But in a good way, I hope.

"As for climbing, if nothing else that last abseil at least felt like an overdue step in the process of finally saying goodbye. It hurts. It really hurts." I think you just described the journey where the only way out, is through.

A deeply moving and powerful account of what it feels like to lose the ability to do the thing you love most and remember the skill that gave your life meaning.

Yet you manage to salvage a memory of that past life and fleetingly experience how it once felt.

An honest an uplifting account from a great writer and human being.